Strata Data Conference

Summary

I attended the Strata Data Conference in San Francisco last week (March 25-28) and summarise what I thought were interesting or thought-provoking ideas I encountered!

The Strata Data Conference brings together hundreds of data people for a multi-day conference featuring tutorials, keynotes, and breakout sessions. Unfortunately I came down with a cold the night before the conference so I wasn’t in top condition for networking, but I still learned a lot from the speakers! Some insights I gleaned over the three-day event:

-

It was interesting to see the different job roles (still within tech) that data touches. Apart from data analysts, engineers, and scientists (which is where my focus perhaps myopically lies), I saw software engineers, managers, and executives for whom data literacy is becoming more and more important. I thought that Strata would be a conference for data scientists/analysts/engineers, but instead there were a wide variety of roles present. While this meant that sometimes topics didn’t get super technical, there was a broad range of topics presented, from cyberattacks to chatbots to using machine learning to improve video-game creation to statistical models for time-series analysis.

-

Spark NLP is a fast and accurate natural language processing library in Python (among a couple other languages) which builds on Spark to allow for distributed/parallel computation. While the pretrained models are easy to use, there is a definite learning curve to using this library for building your own models.

-

One session was specifically about the myriad of ways that job postings could be improved. Long job descriptions (>650 words), especially those written by committee (multiple people adding on requirements or responsibilities) are much less likely to lead to applications. Adding a ‘preferred’ but unnecessary skill to a job posting dramatically decreases the hiring success and increases the time-to-hire for a candidate. Listing these superfluous skills is an additional barrier to entry for those who don’t feel as if they already belong in the domain (especially impactful to women and minorities whose populations are small within tech).

-

Federated learning (computation done ‘on the edge’ with multiple smaller distributed devices, such as cell phones instead of a laptop or server) is a good solution to training models where users are unwilling to share their personal data. An initial model is built on the server, and then an instance is further trained on each node with that node’s data. These updated models are then aggregated back at the server into a better final model, without the server seeing anyone’s individual data.

-

Mixed effects random forests (MERFs) show promise for hierarchical or nested data (e.g. geographical data where city-state-country designations exist). This is exciting since I’m a big fan of random forests.

-

There are a lot of reasons why machine learning models can fail, and a lot of them recall systems ideas. One topic we spent some time on was that deploying the model impacts how the environment (system) behaves (systems idea: every action has side effects; e.g., phishing attacks change as anti-phishing algorithms are updated). Related to that idea was that to catch different fraud schemes, you need to identify many different types of fraud, and/or be able to identify new ones on-the-fly (systems idea: Law of Requisite Variety). Another topic we discussed was that the context of the problem is critical for getting the model built: you can’t just apply the same model to a similar problem (systems idea: problems are general, solutions are specific). A couple other interesting ideas from the talk were that “It’s not about how accurate the model is – it’s about how you can use it” (the machine learning model itself is a small part of the infrastructure that also includes the data collection, verification, monitoring, and other processes – the model has to integrate with all of these in order to be useful), and that in addition to running A/B testing, running A/A testing can be useful to test whether the experiment is proceeding accurately.

-

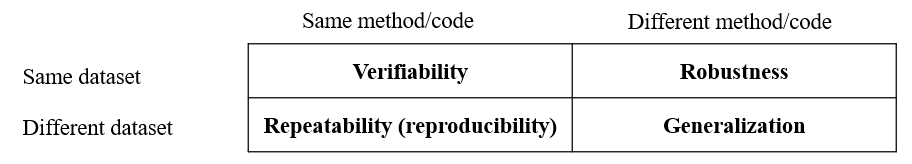

The reproducibility crisis was cast as one quadrant of a two-by-two matrix:

Verifiability is the idea that running the same code on the same data should produce the same results. This is a challenge with stochastic algorithms that produce slightly different outputs between runs, but can be enforced by using the same random seeds.

Repeatability is what people mean by reproducibility: using the same experimental method or the same code on different data (e.g. a different population tested in the same manner). Some solutions that scientists are working on to standardise are pre-registration (defining and documenting the hypothesis and analysis methodology before the experiment), blinded analysis, and working to fight the p < 0.05 cutoff of significance.

Robustness (same data, different methods) presented an especially interesting insight. The speaker presented a slide showing the results of 29 different research teams who given the same dataset and told to analyze it as they saw best. The result was 29 different statistical models with results ranging from a negative likelihood of the variable on the outcome to no difference to a positive likelihood. This problem is especially tough because even though statistics is generally thought of as exact and objective, there’s actually a lot of leeway for which model to choose – and this results in very different results! The suggestion was to run multiple kinds of analyses and aggregate the results of them.

Generalization is the purpose of science, our speaker stated (drawing insights that hold across different datasets and different methodologies), but we didn’t spend much time talking about it.